سيد درويش

|

| Sheikh Sayed Darwish |

Sayed Darwish was born in Kôm

el-Dikka Alexandria on 17 March 1892. During his childhood his family could not

afford to pay for his education, so he was sent to a religious school where he

mastered the cantillating of the Quran. After graduating from the religious

school and gaining the title "Sheikh Sayed Darwish", he studied for two years at

al-Azhar, one of the most renowned religious universities in the world. He left

his studies to devote his life to music composition and singing, then entered a

music school where his music teacher, Sami Efendi, admired his talents and

encouraged Darwish to press onward in the music field.

|

| DARWISH The MUSICIAN |

Darwish at that time was also

trained to be a munshid (cantor). He worked as a bricklayer in order to support

his family, and it so happened that the manager of a theatrical troupe, the

Syrian Attalah Brothers, overheard him singing for his fellows and hired him on

the spot. While touring in Syria, he had the opportunity to gain a musical

education, short of finding success. He returned to Egypt before the start of

the Great War, and won limited recognition by singing in the cafés and on

various stages while he learned repertoire of the great composers of the 19th

century, to which he added ”adwār”

(musical modes) and “muwashshaḥāt”

(Arabic poetic-form compositions) of his own. In spite of the cleverness of his

compositions, he was not to find public acclaim, disadvantaged by his mediocre

stage presence in comparison with such stars of his time as Saleh 'Abd al-Hayy

or Zaki Murad.

After too many failures in singing

cafés, he decided in 1918 to follow the path of Shaykh Salama Higazi, the

pioneer of Arabic lyric theater and launched into an operatic career. He

settled in Cairo and got acquainted with the main companies, particularly Nagib

al-Rihani's (1891–1949), for whom he composed seven operettas that the gifted

comedian had invented, with the playwright and poet Badie Khayri, the laughable

character of Kish Kish Bey, a rich provincial mayor squandering his fortune in

Cairo with ill-reputed women... The apparition of social matters and the

allusions to the political situation of colonial Egypt (the 1919

"revolution") were to boost the success of the trio's operettas, such

as "al-'Ashara al-Tayyiba" (The Ten of Diamonds, 1920) a

nationalistic adaptation of “Bluebeard".

Sayed also worked for Rihani's

rival troupe, 'Ali al-Kassar's, and eventually collaborated with the Queen of

Stages, singer and actress Munira al-Mahdiyya (1884–1965), for whom he composed

comic operettas such as "kullaha yawmayn" ("All of two

days", 1920) and started an opera, "Cleopatra and Mark Anthony",

which was to be played in 1927 with Muhammad 'Abd al-Wahab in the leading role.

In the early twenties, all the companies sought his help. He then decided to start

his own company, acting at last on stage in a lead part. His two creations

("Shahrazad' and "al-Barooka", 1921) were not as successful as

planned, and he was again forced to compose for other companies from 1922 until

his premature death on 15 September 1923.

|

| OLD ARABIC TAKHT |

Darwish's stage production is

often clearly westernized: the traditional takht is replaced by a European ensemble,

conducted by il Signore Casio, Darwish's maestro. Most of his operetta tunes

use musical modes compatible with the piano, even if some vocal sections use

other intervals, and the singing techniques employed in those compositions

reveal a fascination for Italian opera, naively imitated in a cascade of

oriental melismas. The light ditties of the comic plays are, from the modern

point of view, much more interesting than the great opera-style arias. A number

of those light melodies originally composed for al-Rihani or al-Kassar are now

part of the Egyptian folklore. Such songs as "Salma ya Salama”, "Zuruni

koll-e sana marra” or “EI helwa di qamet " are known by all

Middle-Easterners and have been sung by modern singers, as the Lebanese Fayruz

or Syrian Sabah Fakhri, in re-orchestrated versions. Aside from this light

production, Sayed Darwish didn't neglect the learned repertoire; he composed

about twenty muwashshahat, often played by modern conservatories and sung by

Fayruz. But his major contribution to the turn-of-the-century learned music is

better understood through the ten adwar (long metric composition in colloquial

Arabic) he composed.

|

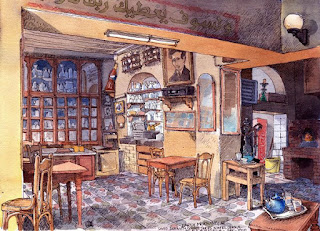

| CAFE DARWISH |

Whereas in the traditional

aesthetics defined in the second part of the 19th century, the "dor" was built as

a semi-composition, a canvas upon which a creative interpreter had to develop a

personal rendition, Darwish was the first Egyptian composer to reduce

drastically the extemporizing task left to the singer and the instrumental

cast. Even the "ahat", this traditionally improvised section of

sighs, were composed by Darwish in an interesting attempt of figuralism.

Anecdotic arpeggios and chromaticism were for his contemporaries a token of

modernism, but could be more severely judged nowadays.

Sayed Darwish was personally

recorded by three companies: Mechian, a small local record company founded by

an Armenian immigrant, which engraved the Shaykh's voice between 1914 and 1920;

Odeon, the German company, which recorded extensively his light theatrical

repertoire in 1922; Baidaphon, which recorded three adwâr around 1922. His

works sung by other voices are to be found on numerous records made by all the

companies operating in early 20th-century Egypt.

|

| Musical instrument Kanoon |

Darwish believed that genuine art

must be derived from people's aspirations and feelings. In his music and songs,

he truly expressed the yearnings and moods of the masses, as well as recording

the events that took place during his lifetime. He dealt with the aroused

national feeling against the British occupiers, the passion of the people, and

social justice, and he often criticized the negative aspects of Egyptian

society.

|

| Gramophne 78 disc Record (1925) Cairo |

His works, blending Western

instruments and harmony with classical Arab forms and Egyptian folklore, gained

immense popularity due to their social and patriotic subjects. Darwish's many

nationalistic melodies reflect his close ties to the national leaders who were

guiding the struggle against the British occupiers.

His music and songs knew no class and were enjoyed by both the poor and the affluent.

His music and songs knew no class and were enjoyed by both the poor and the affluent.

In his musical plays, catchy music

and popular themes were combined in an attractive way. To some extent, Darwish

liberated Arab music from its classical style, modernizing it and opening the

door for future development.

|

| Gazl El Banat original poster |

Besides composing 260 songs, he

wrote 26 operettas, replacing the slow, repetitive, and ornamented old style of

classical Arab music with a new light and expressive flair. Some of Darwish's

most popular works in this field were El Ashara'l Tayyiba, Shahrazad, and El-Barooka. These operettas, like Darwish's other compositions, were strongly reminiscent

of Egyptian folk music and gained great popularity due to their social and

patriotic themes.

Even though Darwish became a

master of the new theater music, he remained an authority on the old forms. He

composed 10 “dawr” and 21 “muwashshat” which became classics in the world of

Arab music. His composition "Bilaadi! Bilaadi!" (My Country! My

Country!), that became Egypt's national anthem, and many of his other works are

as popular today as when he was alive. Sayed Darwish was highly influenced by

his teacher, the great Iraqi musician and singer Othman Al-Mosuli (1854–1923),

and it has been established that his most famous songs "Zuruni kul Sana

Marra", "Talaat Ya Mahla Noura" and "Albint

Alshalabiya" among many others were adaptations from well known works of

Othman Al-Musoli's, who is considered to be the greatest musician and singer in

the modern Middle East. This has cast serious doubt about "Biladi

Biladi" in terms of origin as it has been suggested that Othman also

composed it. It is well known that Sayed Darwish tried his best to show that

everything he played was the result of his own creativity and never admitted to

plagiarism.

Sayed Darwish died on 10 September

1923 at the age of 31. The cause of his death is unknown. Some say he was

poisoned and died from cardiac arrest, others suggest a cocaine overdose. He

now rests in the "Garden of the Immortals" in Alexandria.

Legacy

At the age of 30, Darwish was

hailed as the father of the new Egyptian music and the hero of the renaissance

of Arab music. He is still very much alive in his works. His belief that music

was not merely for entertainment but an expression of human aspiration imparted

meaning to life. He is a legendary composer remembered in street names,

statues, a commemorative stamp, an Opera house, and a feature film. He

dedicated his melodies to the Egyptian and pan-Arab struggle and, in the

process, enriched Arab

music in its entirety.

The Palestinian singer and

musicologist, Reem Kelani, examined the role of Sayed Darwish and his songs in

her program for BBC Radio Four entitled "Songs for Tahrir" about her

experiences of music in the uprising in Egypt in 2011.

Sayed Darwish put music to the

Egyptian national anthem, Bilady, Bilady, Bilady, the words of which were

adapted from a famous speech by Mustafa Kamel.

Coincidentally, on the day of his

death, the national Egyptian leader Saad Zaghloul returned from exile; the

Egyptians sang Darwish's new song "Mesrona watanna Saaduha Amalna",

another national song by Sayed Darwish that was attributed to "Saad"

and made especially to celebrate his return.